For many of us, the early pandemic played out on the screen in the palms of our hands. We relayed updates about our lives over text rather than coffee, FaceTimed with hospitalized loved ones rather than visiting them, and watched friends marry via live feed rather than in a chapel. FRONTLINE’s interactive team wanted to tell a story about the pandemic that unfolded on a screen in ways true to the reality of the people involved.

For many of us, the early pandemic played out on the screen in the palms of our hands. We relayed updates about our lives over text rather than coffee, FaceTimed with hospitalized loved ones rather than visiting them, and watched friends marry via live feed rather than in a chapel. FRONTLINE’s interactive team wanted to tell a story about the pandemic that unfolded on a screen in ways true to the reality of the people involved.

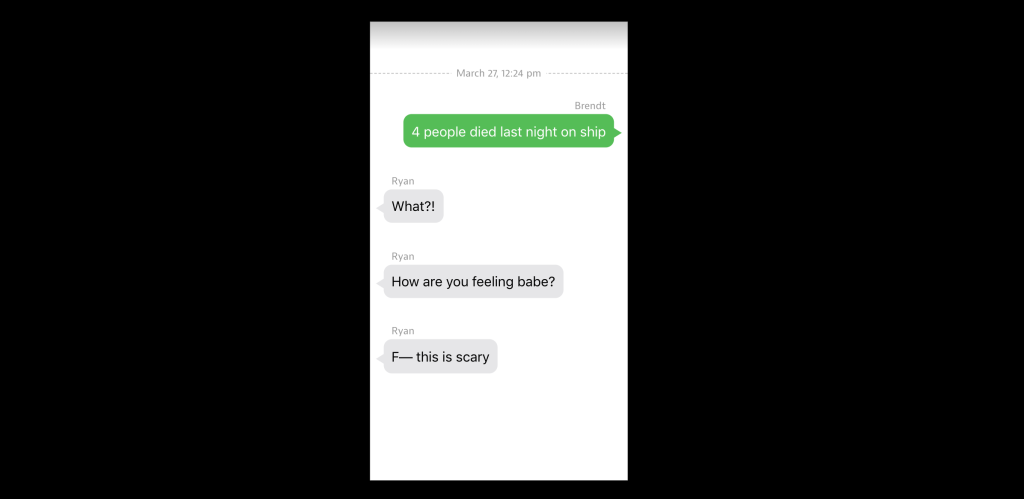

Drawing on the text messages, social media posts, cell phone videos and journal entries of a passenger trapped aboard a cruise ship where COVID-19 was spreading, FRONTLINE’s breakout interactive The Virus at Sea tells an intimate story of love and terror.

As the audience learns, passenger Brendt Reil, a performer from New York, believed he was embarking on his dream vacation when he boarded the cruiseliner Zaandam at the beginning of March. But as the virus spread and nations closed their borders to cruise ships, the voyage turned into a deadly nightmare for Brendt and became deadly for others stuck aboard. Brendt spent weeks in a windowless cabin battling to breathe, his intermittent internet connection his tether to the outside world and, he would argue, to his sanity.

Reporter and producer Katie Worth obtained extraordinary access to thousands of text messages exchanged in those weeks by Brendt and his partner, Ryan, who had remained in New York, as well as Brendt’s cell phone videos, social media feeds and journal entries. The story that emerged, through weeks spent curating this wealth of source material, captures the sense of disquiet and danger that pervaded the earliest days of the pandemic.

The Virus at Sea is at heart a love story — a simple, human account of a couple enduring an alarming and deadly ordeal. But it is simultaneously a piece of rigorous original journalism. The Virus at Sea elucidates the human cost of the decision by cruise operators to launch ships, even as a pandemic spread. Crucially, the project sheds light on the reality that while passengers were eventually allowed to leave the ships, many crew members were not. For months, ports around the world refused to allow crews to disembark and fly to their home countries. We contacted cruise operators around the globe and exposed the stunning truth that as of publication in July, more than three months after the industry had returned all of its passengers to port, 52,000 cruise laborers remained stuck on ships and unable to go home.

The Virus at Sea is at heart a love story — a simple, human account of a couple enduring an alarming and deadly ordeal. But it is simultaneously a piece of rigorous original journalism. The Virus at Sea elucidates the human cost of the decision by cruise operators to launch ships, even as a pandemic spread. Crucially, the project sheds light on the reality that while passengers were eventually allowed to leave the ships, many crew members were not. For months, ports around the world refused to allow crews to disembark and fly to their home countries. We contacted cruise operators around the globe and exposed the stunning truth that as of publication in July, more than three months after the industry had returned all of its passengers to port, 52,000 cruise laborers remained stuck on ships and unable to go home.