I found out about my dad’s arrest reading the news. Now I help families like mine.

One day when I was 15 years old, my dad didn’t come home. That day, my aunt and cousin came over to watch my younger siblings and me while my mom went to her second job.

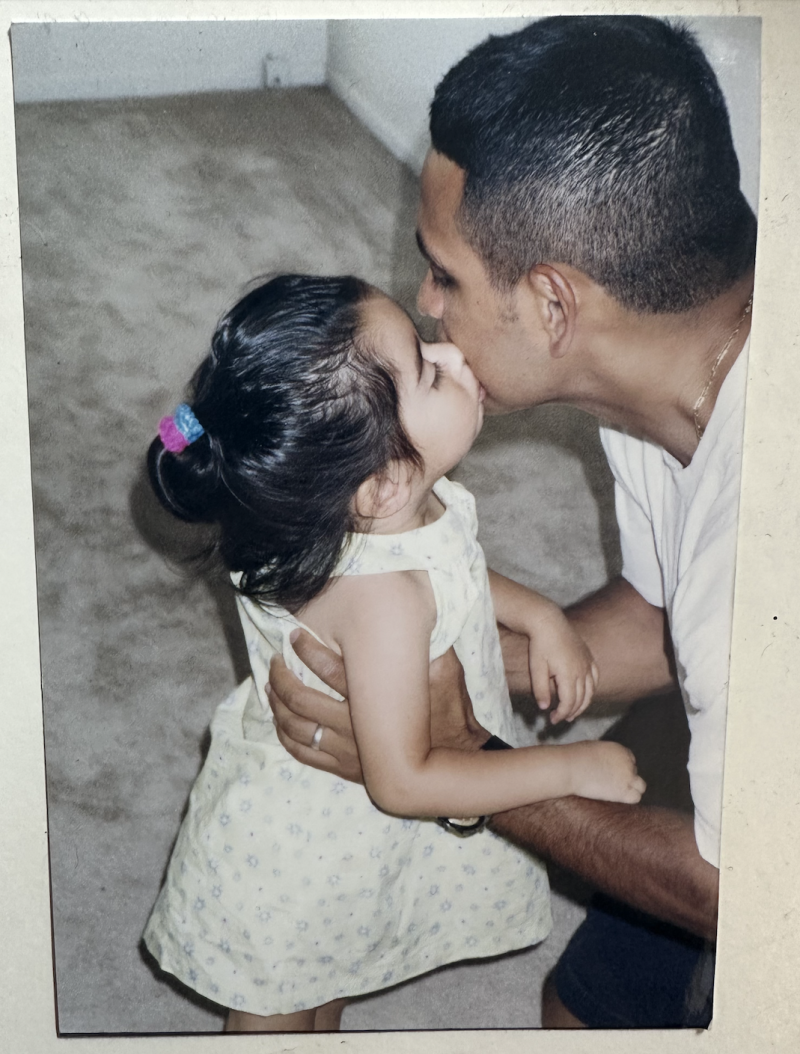

My dad was always home by the afternoon. It was like clockwork, and I couldn’t get over his absence. I was homeschooled and my dad was there most of the time. It was always the two of us against the world.

“Where is Dad?” I asked my aunt.

“We don’t know.”

The day went on that way. As a quintessential Gen Z-er who turns to the internet for everything, I took my search to Google. The headlines had the answer: my dad was arrested on his way to work, and he was facing life in prison.

Journalists hounded my mom at work—and while they never showed up at our home—it was a constant worry. The news of my father’s arrest rippled through the community. He was our local sports coach and an avid church volunteer. Everyone knew him—but after those articles came out, they forgot his contributions and only spoke of his arrest.

My mom kept my siblings home from school for a week—waiting for the news to die down—but that only held off the inevitable. Journalists weren’t thinking about the ripple effect it might have on us and what we would have to live with long after their story was published. As I started to visit my dad in prison and learn of the conditions facing incarcerated people, my resentment of the media only grew.

Journalists can be so quick to cover arrests and trials that changed peoples’ lives, but they rarely follow through on what happens after the arrest. Criminal justice reporting seemed to solely consist of cops and courts, but few outlets looked into the implications and conditions afterwards.

When I started at the University of Southern California during the pandemic, studying journalism was the last thing I expected to do. I was intimidated by the largely white and wealthy campus, but working at the Daily Trojan seemed like a way to gain some respect.

I was hired as a newswriter, and I started to focus my work on local student-run nonprofit organizations and positive impact. I had so many bad experiences with the media that I wanted to tell stories that were empowering and highlighting the contributions that students of color were making to the school. In a sense, it was almost like reclaiming my power by changing the narrative and lens through which stories were being told.

Still, I didn’t really come into my niche until later that semester when I started a job finding additional evidence on a wrongful conviction death row case, where I spent long nights digging through dozens of court transcripts and gaining an understanding of the post conviction legal landscape. I appreciated the work in this job because it felt thorough and responsible, that we were looking into every possible avenue, lead and piece of evidence that could exonerate this man who claimed to be innocent. The alternative was the regurgitated police that had gone out to the press. This work was the first time I realized that I could do investigative reporting to dig into the issues that other journalists disregarded or where they only scratched the surface.

A few months later, I started an internship with BuzzFeed News. Within the first month, I pitched a story on the pandemic’s effect on family visitations in prison. Families like mine weren’t able to visit their loved ones in prison, and I wanted to cover the impact that had on connections, mental health and recidivism. I knew this was happening because my own family was experiencing it—we had no idea when we would see my dad again.

I knew my family wasn’t the only one experiencing frustration and confusion, so I started digging. I found a larger issue of patchwork policies and a growing trend of increasing restrictions on families and their incarcerated loved ones. Families were eager to speak with me because they felt safe and knew I understood their experiences. In the process I tried keeping them up-to-date so they would feel more comfortable. The story reached a national audience and many people who had family in the system later reached out to me to thank me for “telling it how it is.”

Although I’m still a student and have a lot to learn, I let my experiences with the media inform my reporting. Most recently, I worked with The Marshall Project to create an engagement project that highlights the way that families stay connected during incarceration. It gives a direct voice to the people experiencing these issues first hand, and let’s them tell their own stories. It was a cathartic experience for me, and I want to continue to push forward the kind of journalism that uplifts and gives a voice to these communities.

Covering criminal justice issues with my father still in prison is difficult. When I was reporting on California’s prison immigration policies, I found out that my father was among the list of people referred to the U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement for verification of citizenship. Having to move forward with the story while remaining objective was emotionally taxing and I wanted nothing more than for the story to be over. I came close to quitting journalism, but I had unconditional support from my colleagues at ScheerPost and the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

Ultimately I was able to use the knowledge from my reporting to knew how to proceed to get his ICE hold removed and will use that to hopefully save him from deportation. Because I did the research, the information will help other families as well.

I want to make things better for other people, especially children growing up like I did. If I can help normalize coverage on prison conditions and show people the human toll on those impacted by the criminal justice system, maybe society will be a little more forgiving and accepting. Regardless, I want to empower families to feel like they have a voice in this coverage.

There is surely another fifteen year old girl out there, wondering where her dad is and if he will ever come home. I want to make things better for her.