Immersive Case Study: Actual Reality

Published July 10, 2020

This case study is part of the broader Guide to Immersive Ethics. Learn more in the overview, including what ethical criteria to consider when starting a new immersive project.

At McClatchy, we built our own ethics code for our AR app, Actual Reality, while we were early in pre-production for the content. Creating stories in AR was a first for our organization, so we wanted to set some ground rules before getting started. What follows is a slightly abridged version of the editor’s note that appears in the “about” section of our app. The note was written by executive producers Ben Connors, Theresa Poulson and Meghan Sims, based on the collaborative efforts of Jayson Chesler, Cassandra Herrman, Eric Howard, Melanie Jensen, David Martinez, Stanley Okumura, Andrew Polino, Julian Rojas, Kulwinder Singh, Kathy Vetter and Nani Sahra Walker.

The editor’s note

Our AR stories use a variety of 3D media, including photo-realistic models, recreations and illustrations. The production processes are new to nonfiction storytelling. Maintaining your trust in our journalism is of the utmost importance to us, so we will be transparent about how and why we produce the 3D images you see in this app, including clearly noting instances where there might be confusion.

Photo-realistic models

The photo-real, 3D models of people, places and objects are created using a process called photogrammetry, which combines hundreds of photographs taken from many angles.

The photo-real, 3D models of people, places and objects are created using a process called photogrammetry, which combines hundreds of photographs taken from many angles.

Due to the nature of the technology, many of these models are edited for technical and visual clarity. We follow these guidelines when editing those objects:

To maintain faithful representations of people, places or objects, some of the visual information that was lost or damaged in the production process has been reconstructed by replicating the texture and shape of the original object.

When a photo-real, 3D object cannot be reconstructed, we might use an artist’s recreation in its place. We have done this only if:

- The object is integral to the story,

- Using a recreation is the only option for representing the object in the story and

- The recreation is as faithful to the original object as possible.

Any time we’ve used a highly realistic artist’s recreation to take the place of an object, it is noted at the beginning of the story you’re viewing.

Photo-realistic scenes through recombination

When a scene contains different types of 3D models, particularly models that move, it is often necessary to scan different components of the scene in isolation (separated either in time, location or both) and then recombine them to produce a single, cohesive scene.

For instance, we might spend 20 minutes capturing a 3D model of a street corner, then afterward ask a character to step into a different area where we can most effectively create a model of their body. Then we’d recombine those elements to create one scene.

When we use recombination to create a scene, we endeavor to recreate the scene with as much fidelity as possible making sure that:

- The scale of the components match,

- Any actions represented are authentic to the characters and the spaces they are in,

- And no objects of editorial significance are omitted.

At times, we will create recombinations that are not intended to represent actual environments, such as when we show how objects compare or show several objects as a gallery. These instances will be clearly noted in the editor’s notes for that story.

Motion capture

In some cases we have added movement to photo-realistic, 3D people through a process called motion capture, to provide lifelike representations of the sources in our stories. To do this, we:

- Record motion data with a portable sensor,

- Take hundreds of photographs from many angles (photogrammetry) and

- Combine them in software to create a moving, 3D model.

As we experiment with this new technology, we aren’t always successful at capturing the real motion data, so we might use animation from a stock library to add movement to a person instead. Any time we do this, it is noted at the beginning of the story you’re viewing.

Volumetric video

In some cases we’ve presented characters using a technology called volumetric video. We use a tool called DepthKit, which combines frames from two different types of video cameras. One camera records normal color videos and the other records a low-resolution “depth” video that captures the shape of the character in 3D.

In some cases we’ve presented characters using a technology called volumetric video. We use a tool called DepthKit, which combines frames from two different types of video cameras. One camera records normal color videos and the other records a low-resolution “depth” video that captures the shape of the character in 3D.

Although you can move around these videos and view them from multiple angles, you might notice that the edges of the characters look warped from certain perspectives. To mitigate the effect, we’ve slightly altered the brightness of the color video with information from the depth video. You’ll be able to see the depth video overlaid as a series of light lines and dots. The resulting image looks a little like an animated topographic map.

Illustrations

You’ll also see different kinds of artists’ illustrations throughout this app.

You’ll also see different kinds of artists’ illustrations throughout this app.

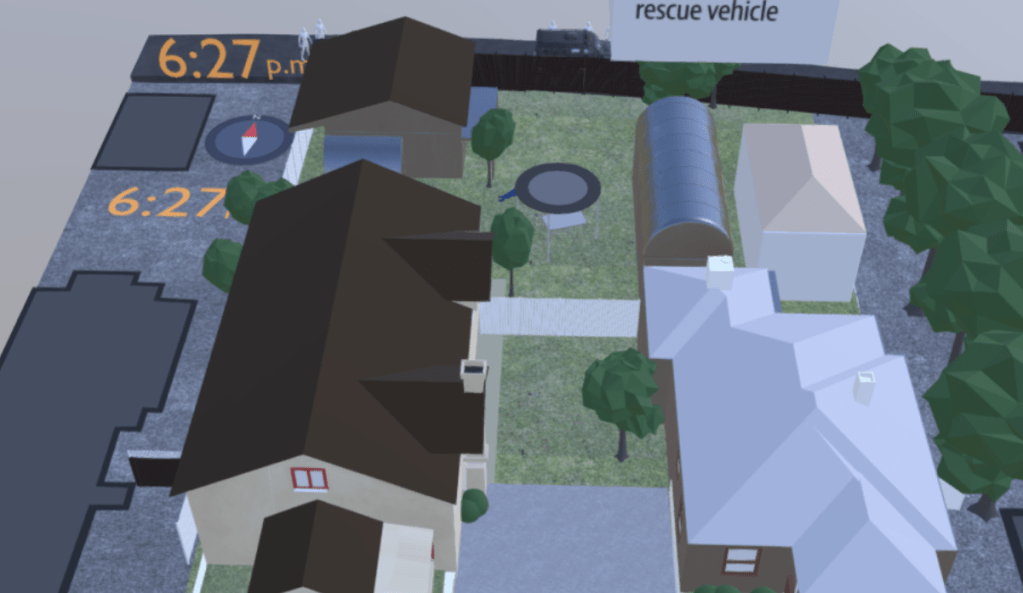

The illustrations are used for a variety of reasons: to create a sense of space, to recreate a memory, when a realistic reconstruction wasn’t possible (either due to lack of access and/or privacy concerns), to contextualize or add to a realistic 3D object, to visualize data or represent a concept.

These illustrations should be easy to differentiate from the realistic, photogrammetric objects. But we’ll err on the side of caution: Any time we think there might be a reason to clarify or add context to what you’re seeing, we’ll let you know in a note at the beginning of the story you’re viewing.

Build Your Own Guide

Some things to consider when making your own guide:

- Reference precedent: Consider your organizations’ rules for photography, graphics, video and design.

- Dialogue across disciplines: Immersive media requires significant contributions from talent with diverse professional backgrounds. Include all contributors in conversations about your journalistic standards, not just the ones who traditionally get the bylines.

- Practice transparency: Emphasize why you are using this technique (doesn’t have to be explicit). Provide explanations for your audience for those who want it. Choose language carefully. Who are you talking to and why?

- Embrace imperfections: Shortcomings in technology and the “rough edges” that come with experimentation shouldn’t hold you back.